Personal responsibilities and mental wellness may seem like different conversations.

After all, the world is seeing record levels of burnout, anxiety and exhaustion — partially resulting from our overwhelming lifestyles, never-ending to-do lists and unforgiving schedules. So how could adding more responsibilities improve things? How could having additional duties benefit our mental health?

Jewish scholars have been asking these questions for thousands of years, and they are particularly pertinent to the upcoming period of “hitbodedut” (self-reflection) and “tikkun hanefesh” (improvement of the soul); the months of Elul and Tishrei provide ample opportunities to rebuild, reinvigorate and pivot. The holidays that take place within these months — Rosh HaShanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot and Simchat Torah — as well as the liturgy, traditions and culture surrounding them, all emphasize people’s mental wellness via “understanding with their heart, return[ing], and be[ing] healed” (Isaiah 6:10).

Achieving an understanding of our hearts is no small feat, but if it is a first step to healing, we must work toward that goal. Practices such as mindfulness and meditation can be important guides to help us understand our internal worlds. The Jewish concept of “cheshbon hanefesh” — an accounting of the soul — can also aid with this enlightenment.

A cheshbon hanefesh is not as spiritual or ephemeral as its translation sounds. We practice different types of cheshbonot every day: When we check our credit card statements and resolve to work harder on our spending; when we realize we scroll on our phone for too many hours a day and install a time-management app; or when we recognize the ways we could be a better friend to someone who’s struggling. Similarly, a cheshbon hanefesh is an analysis of the ways in which we can do and be better to ourselves (which, of course, can have an impact on the world around us).

This may sound like the idea of a New Year’s resolution, and in many ways it is. The Jewish new year is a great time for reflection. It provides a benchmark by which we can measure our progress and see if our goals have changed, and it allows us to think about how best to move forward based on what has worked and what hasn’t. That kind of clarity and self-acceptance can help us progress in our mental health journeys with intention and resolve, and it can feel deeply cleansing to engage with honesty and awareness.

Maybe you’re convinced and want to give cheshbon hanefesh a try. There’s no “right way” to do it, but here are some places to start:

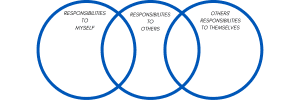

- Assess the responsibilities you have to yourself, those you have to others and the ones others have to you. Are you meeting these responsibilities? Are others in your life meeting them?

Taking responsibility starts with the recognition that we all have some power and ability to affect others, and every person has some capacity to affect the world. We have responsibilities to ourselves: Developing our mental wellness, keeping our spaces clean, working hard, managing our time and being honest. Other people have the same responsibilities.Then there are the responsibilities we have to others. They can be small, like saying “please” and “thank you” or throwing cans into the recycling rather than the garbage can. Or they can be big, sometimes very big, such as not letting people fall through the cracks or stepping up and taking a stand when we see wrongdoing.

A powerful quote from Pirkei Avot posits “[we] are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are [we] free to desist from it” when it comes to our responsibilities to others — and especially for those we have to the world.

Ask yourself if you are engaging realistically with your responsibilities. Are you able to manage them? Which ones are truly essential? Which people and environments support (or hold back) the fulfillment of these responsibilities? Below is a Venn Diagram that can help with this exercise.

- Write a “personal mission statement.” In Greg McKeown’s bestselling book Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less, he writes about the ways we can achieve clarity and increase opportunities for joy within ourselves. One of these tools is the personal mission statement.

When a company or organization is struggling over what direction it should take, it oftens turns to its mission statement. Similarly, writes McKeown, we can create our own mission statements to help us determine the right path when we are conflicted or confused.

A good personal mission statement should be:- Concrete — specific and narrow enough that you can plan properly

- Measurable — with a beginning and end you can measure your progress against

- Attainable — realistic and doable given your skill-set and abilities

- Inspiring — allows you to strive toward something bigger than yourself

McKeown encourages those struggling with this lofty set of adjectives to ask themselves two questions: “If [I] could be truly excellent at only one thing, what would it be?” and “How will [I] know when [I’m] done?”

- Look back and see where you were last year. Yes, really! Sometimes going backward for self-reflection can be tremendously helpful in knowing what’s next. Look back on the achievement of last year’s goals — and the things that affected their achievement, positively and negatively.

Like with any mental wellness practice, the goal is not to judge your progress but to observe it. Look for “cause and effect” over the last year, and reflect on why you may have been able to complete certain priorities and resolutions over other ones. There are many reasons we do and do not achieve the things we set out to do, including some of the following:- They aren’t realistic. Sometimes we set goals that are too big or unattainable, given the place we are in life. It can help to work toward those goals by breaking them up into small chunks: If we want to learn guitar, we should start by learning how to play the chords and read music rather than aiming to play a very advanced song within a year.

- They don’t make us happy or bring us joy. In Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything, author B.J. Fogg recommends creating a celebratory routine that supports us in creating change. It may feel silly, but recognizing each moment we make progress by doing a fist-pump in the air or a little dance can help condition feelings of positivity toward our goals.

- They aren’t supported. The environments we are in play a large role in achieving our goals. If we are looking to work on intuitive eating, being around people who fuss about calories and dieting is likely to disrupt our progress. If we want to work on the skill of positive self-talk, it may not be helpful to be in a social environment where people speak negatively about others. One of the most helpful examples of “cause and effects” comes from the places and people that affect our goals. Sometimes, in looking to make progress, it’s important to shake things up and seek new experiences or relationships.

If you can make the time over the next few weeks, find a quiet space, take a pen and some paper, and give yourself respect and self-acceptance as you reflect. May you use cheshbon hanefesh as a tool for making your entry into the Jewish new year feeling clear headed, recharged, hopeful and mentally well.

Ruthie Hollander was born in Germany, grew up in Michigan, and has spent the last six years in the tristate area. She is happiest when she’s creating. An employee of several Jewish nonprofit organizations and a resident of the Upper East Side of NYC, she feels endlessly grateful for her husband Max, their high-strung dog Momo and high-energy baby Mila, and an abundance of books and plants (not necessarily in that order).

Ruthie Hollander was born in Germany, grew up in Michigan, and has spent the last six years in the tristate area. She is happiest when she’s creating. An employee of several Jewish nonprofit organizations and a resident of the Upper East Side of NYC, she feels endlessly grateful for her husband Max, their high-strung dog Momo and high-energy baby Mila, and an abundance of books and plants (not necessarily in that order).